- Home

- Michael M. Greenburg

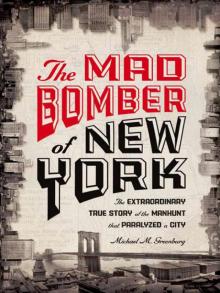

The Mad Bomber of New York Page 2

The Mad Bomber of New York Read online

Page 2

Across America people began to ask, who is this person, this Mad Bomber, and what does he want? And in New York City, Police Commissioner Stephen P. Kennedy announced “the greatest manhunt in the history of the Police Department.”

I

“A REAL BOOM TOWN”

THE CALL CAME IN TO THE 20TH SQUAD OF THE NEW YORK CITY POLICE Department, located on the upper west side of Manhattan. Shortly after noon on November 18, 1940, an employee of the Consolidated Edison Company, in one of a maze of Con Ed buildings located within the West Sixty-fourth and Sixty-fifth Street city blocks bounded by Amsterdam and West End Avenue, had come across a curious sight while on break from his duties. A small wooden toolbox had been left on a second-story windowsill, containing a length of iron pipe about 4½ inches long and neatly capped on each end. Upon further examination, the employee observed what appeared to be a sheet of paper wrapped around the pipe. Not particularly alarmed by the article—a pipe in a toolbox was not an especially ominous sight at a power delivery company—the employee grasped the object and began unraveling the sheet.

There had been a chill in the air all morning long, and it promised to be a raw and sunless day throughout. As the employee opened the sheet of paper his pulse immediately quickened and, though comfortably shielded from the elements, the cold of the day shot through him like a charge. There, in neatly printed block lettering, appeared the words

CON EDISON CROOKS, THIS IS FOR YOU.

Then, printed in what appeared to be a coarse grey substance (which upon later analysis proved to be gunpowder) was ominously written

THERE IS NO SHORTAGE OF POWDER BOYS.

Carefully, the employee set the device back into the toolbox and scurried for his superiors, breathlessly exhorting them to call the police.

The New York City Bomb Squad was in no mood for pranks. Five months earlier, on July 4, 1940, a suitcase containing sixteen sticks of dynamite had been found at the British Pavilion of the World’s Fair held in Flushing Meadows, New York. While being examined on the outskirts of the fairgrounds, the container exploded, killing two bomb squad detectives and critically injuring two other police officers on the scene. Though the explosion was felt throughout the 1,260-acre park, most of the holiday throng mistook the blast for a rather raucous feature of the patriotic celebration. For the New York City Bomb Squad, however, the tragedy would have broad implications. Following World War I, the squad took on the name Bomb and Radical Squad and focused its efforts on the militant leftists that threatened the city in the early 1920s. In 1935, as a result of duplication of effort in analyzing threatening and hostile writings, the bomb squad merged with the forgery unit to form the Bomb and Forgery Squad. Following the World’s Fair tragedy, not only would the bomb squad be restructured into its modern incarnation as an independent entity, but it would forever adopt the operating procedure of allowing not more than one member of the squad to examine any device at any one time.

Despite the immediate roundup of “agitators and other suspects,” the World’s Fair bombing was never solved. Adopting a more rigorous training program and specialized protective gear, the bomb squad, mourning its own, would continue its mission with a greater sense of vigilance and purpose, and, for the next sixteen years, it would be tested at every turn. Among police, the work of the squad would be called “the world’s most dangerous job.”

The precinct officers who arrived at the Con Ed building at 170 West Sixty-fourth Street on November 18, 1940, immediately knew they were beyond their pay grade after observing the length of pipe in the toolbox. A call from headquarters went out to the bomb squad, and until the squad’s arrival the officers on the scene secured the area and waited for what seemed like an eternity.

Upon arriving at the scene, the squad detectives assigned to the case immediately understood that they were indeed dealing with an “infernal machine”—a device, typically homemade and “‘maliciously designed to explode and destroy life or property,’ which can be deactivated by a man (other than its maker) only at the peril of death.”

Knowing this, the detectives acted strictly in accordance with squad procedures. As one detective stated, the difficulty was that “[E]very problem is a new one. Every infernal machine is different. The ones that work on acid, the ones that work on a watch, the ones that work on position. We get the people away and then figure what we’re going to do.” Exactly what the New York City Bomb Squad, a team of eight to ten specially trained, dedicated volunteers, would do involved an often harrowing process of evaluation and removal, which would be performed in the coming years more times than any of them—or their wives and children—cared to dwell upon.

The preference of the bomb squad detective was almost always to detonate any small device bearing a volatile trigger mechanism on the scene if at all practicable, once the area had been fully cleared and evacuated. Though it was not the best outcome for the property owner, since the explosion would almost certainly result in damage, detectives preferred a controlled detonation on their own terms, rather than an explosion at an unexpected time on the bomber’s terms. In some cases the device was simply nudged or “teased” with a long poker by a shielded officer, and at other times a length of twine was attached and, from a distance, yanked to agitate or incite a response. Creative methods to test devices and provoke detonation were routinely employed, and all carried their own distinct set of hazards and risks.

The Con Ed employee had already handled the pipe found at the West Sixty-fourth Street location and removed the handwritten note that previously surrounded it, and thus it was fairly evident that this was not a so-called position-control bomb—one that is set off by movement, drop switch, or liquid. Nonetheless, slowly and meticulously one detective approached the device and listened for the barely audible ticking of a timing mechanism. Having heard none, he used a device consisting of a gripping mechanism placed at the end of a five-foot pole operated by a handle at the reverse end—a bomb squad staple. Wearing protective body armor, steel-mesh gloves and shoes, and a steel-plated bucket-shaped helmet, and shielded behind a sheet of bullet-proof glass, the detective carefully turned the device over.

“Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, the innocent-looking object is just what it looks like—innocent,” recounted one bomb squad detective. “It’s that one in a hundred that sprays a quarter pound of rusty steel into you.” To the detective’s relief, his prods failed to detonate the device, though he knew the danger was far from over.

Once it was determined that the object was not reactive to movement, it was carefully placed into a woven steel-cable bag, which had come to be known affectionately as the “envelope,” and carried out of the building at the center of a fifteen-foot pole manned on either end by two armored squad detectives. The package was then safely deposited into a specially equipped containment truck and transported with a blaring escort of police motorcycles and emergency vehicles to a secluded area for detonation or simple further analysis. The vehicle, officially named the Pyke-LaGuardia Carrier for the police lieutenant that conceived of the idea and the sitting mayor of New York, was a fifteen-ton semitrailer flatbed truck outfitted with a monstrous arched cage constructed of 5/8-inch-thick woven steel cable left over from the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge. Introduced shortly after the World’s Fair bombing, the vehicle was “designed to take a bomb from a congested area to a remote or suburban district and to do so in a manner that will protect the public and the police.”

Removed to the relative safety of an isolated location, the Con Ed object was dusted for fingerprints and then suspended in a vat of motor oil to clog the moving parts of any timing mechanism and to prevent an electrical or chemical reaction so that further examination could be conducted. Though the technique would in later years fall into disuse, it was for a time considered helpful in the detection and neutralization of bomb components. In a typical situation, an earphone, similar to a doctor’s stethoscope (which would still operate in oil) would be applied to the devi

ce to determine if its timing mechanism, such as a ticking watch, had been disabled by the oil. Once satisfied that any dangerous internal apparatus had been neutralized, another technology adapted by police officials after the World’s Fair tragedy, the fluoroscope, could be used to X-ray its contents. Only then could bomb squad detectives make a definitive pronouncement on the hazards of the device.

Having undertaken these procedures in the Con Ed incident, and confident that the imminent danger had passed, the officers transported the object to the police laboratory, located at the Centre Street headquarters in Manhattan, for further analysis. While the neatly capped pipe casing did contain some typical bomb components such as a flashlight bulb, a battery, a steel spring—and curiously an atypical Parke-Davis throat lozenge (the significance of which would remain a mystery to detectives for years to come)—technicians agreed that the device itself was imperfectly constructed and incapable of detonation. The question then became who had placed the bomb and why.

Con Ed, as it is today, was a large conglomerate company employing thousands and serving millions. While it was clear to all that the person who planted the device bore some grudge against the company, the task of identifying that person through the Con Ed system of record keeping would prove all but impossible. Many of the company’s files, dating back decades, were housed in vaults and warehouses scattered throughout the city without method or organization. To make matters worse, each of the nearly two dozen separate entities that had merged to form the power conglomerate in the mid-1930s had maintained its own set of records, many of which were long since lost or destroyed. Within the company headquarters itself, the more recent claims of disgruntled and angry employees littered the personnel department record room, and hundreds of customer complaints poured into the company daily. The device could have been laid by almost anyone, and even the most painstaking search of the records, it was theorized, could never pinpoint a suspect. And so the police investigation ended, without result, as quickly as it began. “The episode was filed and forgotten.”

Serial bombings as a cultural phenomenon were not new to New York, or America as a whole, in the early to mid part of the twentieth century. As far back as 1906, a so-called Italian squad, the first incarnation of the bomb squad, had been formed as an arm of the New York City Police Department for the sole purpose of protecting the Italian immigrants of the city from the extortionist methods of a clandestine underworld cartel calling itself the Black Hand. The ex-convicts and outlaws that made up the group preyed on immigrant populations, blackmailing and extorting payments with threats of murder, certified with sticks of dynamite. “Recognizing the inability of the present small force of Italian detectives to drive out these criminals,” wrote the New York Times, “Police Commissioner Bingham ordered . . . the organization of a secret service which is expected to be recruited and conducted as secretly as the operations of the men against whom it will work.”

In 1908, just two years after the formation of the squad, police had apprehended five men, including the “master bomb-maker for the Black Handers.” Among the evidence uncovered by the raid was a book containing carefully drawn diagrams and formulas for the manufacture and placement of explosive devices. “The book is not mine,” said the captured bomber. “I know nothing about it. I am an honest grocer. I do not know the Black Hand and I do not make bombs.” Less than a year later, Lieutenant Giuseppe Petrosino, the first commissioner of the Italian squad, was murdered in a town square in Palermo, Sicily, while investigating the notorious band.

With the approach of American involvement in World War I, concern over domestic bombings took on a more geopolitical and militaristic quality. By 1914, the New York City police commissioner had taken all bomb-related matters from the Italian squad and placed them under the jurisdiction of the newly created bomb squad. As German espionage efforts ensued in New York, the central focus of the squad became the protection of allied assets bound for Europe and the preservation of American neutrality. With America’s entry into the war quickly becoming an inevitability, however, the bomb squad was placed under the direct control of the War Department.

Anxiety over the German espionage campaign in the United States culminated in 1916 with the sabotage and destruction by German agents of a munitions depot in New Jersey called Black Tom, located on a promontory extending into New York Harbor. The series of explosions was so powerful that the Brooklyn Bridge wavered and windows shattered in the buildings of lower Manhattan. The investigation and the ultimate assignment of blame for the Black Tom bombing was argued and litigated for years, but what is absolutely clear is that by the end of World War I the American public had become accustomed to the reality of random bombings that killed and maimed without discrimination.

By 1919 America’s anxiety over domestic terrorism would shift from the work of militaristic spies to the radical statements of anarchists and foreign leftists. In April 1919 militant followers of the outspoken revolutionist Luigi Galleani, the so-called Galleanists, deposited into the mail dozens of bombs intended for prominent American politicians, officials, and capitalists. Though the devices were discovered and ultimately defused, a few months later a similar coordinated attack was successfully carried out across eight American cities, where explosives ripped through the homes of a series of government officials including various congressmen and the attorney general of the United States. Anarchist literature and leaflets were strewn about the sites of each bombing, proclaiming that the “revolution” had begun. Then, on September 16, 1920, a horse-drawn cart laden with one hundred pounds of dynamite exploded on Wall Street in front of the headquarters of J. P. Morgan Bank, instantly killing thirty people and injuring hundreds more. Shortly before the explosion, flyers were found in a nearby mailbox with hand-stamped red lettering reading:

REMEMBER

WE WILL NOT TOLERATE

ANY LONGER

FREE THE POLITICAL

PRISONERS OR IT WILL BE

SURE DEATH FOR ALL OF YOU.

AMERICAN ANARCHIST FIGHTERS

The backlash was both harsh and predictable. These bombings, juxtaposed against the patriotism and nationalist pride generated by World War I, would be the catalyst for the systematic xenophobic assault of immigrants, socialists, and left-wing groups across America. Though based on the palpable fear of radical insurrection, the “Red Scare” would envelop the country and evoke a period of civil rights violations that would endure from 1918 to 1920.

Through the ensuing years, most of the incidents involving planted explosives involved lone reprobates with unexplained motives or racketeers hurling “pineapples” at one another from moving vehicles. The rash of political bombings that would mark later decades would strike New York with harsh and bewildering force. Left-wing militant groups issuing declarations of war against the power structures of America would prompt one New York police commissioner to declare that the problem had reached “gigantic proportions.” The New York Times would describe the city as “[a] real boom town.”

In the days following the Con Ed incident, the Bomber anxiously scanned newspaper after newspaper searching for any mention of the unit that he had quietly placed on the windowsill of the West Sixty-fourth Street office building. Though some sources have concluded that the device was a live explosive filled with volatile black powder, the evidence appears to indicate otherwise. “It wasn’t loaded. It was complete, but instead of powder, there was a note,” he would later explain. “It was a[n] empty bomb.”

Knowing that the writing would have been obliterated by the force of a detonation, police theorized that the culprit either inserted the note to satisfy some inner compulsion, aware that it would be destroyed, or that the bomb had been purposely constructed to deliver nothing more harmful than a sinister message to its recipient. The Bomber’s own words would suggest a non-lethal intent. “That first unit was just a sample of what was to come.”

War was raging in Europe and the American public and media were focused on oth

er, more pressing, matters. To the Bomber’s dismay, his handiwork would never find its way into the newspapers. He gained no satisfaction from the “message” that he had served upon the power company, feeling instead that it had been ignored and even ridiculed. The lack of public interest in his initial bomb-making endeavor served only to anger and embolden the already seething miscreant. He knew that further steps would have to be taken to focus the world’s attention on the misdeeds of the corrupt Con Ed.

On September 24, 1941, traffic in and about the area of Nineteenth Street between Fourth Avenue and Irving Place was disrupted by the discovery of a strange object in the roadway. Crammed into a red wool sock was a contraption similar in construction and appearance to the pipe bomb found the previous November on the Con Ed windowsill. Though there was no note or identifying markings, bomb squad detectives quickly recognized the neatly capped four-inch length of galvanized pipe—and, once again, the inexplicable throat lozenge. This, coupled with the fact that the object had been placed within mere blocks of the main headquarters of Con Ed at 4 Irving Place, led them to the inescapable and disturbing conclusion that both devices had been conceived and assembled by the same individual.

The Mad Bomber of New York

The Mad Bomber of New York